December, 10, Mystetsky Arsenal launches the exhibition What is your name dedicated to the problem of internally displaced persons in Ukraine. The project curator Katia Taylor tells Platfor.ma about how Ukrainians had become too accustomed to the bad news to even take notice, and about the assistance to displaced persons as a real humanity.

Picture: "Odіssea Donbas" Project

Picture: "Odіssea Donbas" Project

Eighteen months ago, I went to the East to see how people live during the war. I wanted to bring them humanitarian assistance and to consider what else we can do for them. It was the most terrible and dramatic journey in my life.

By that time my parents had moved from Luhansk to Kyiv and have been living there for more than a year. The war had continued for this period but a year is too little time to begin forget the tragedy if it does not concern you personally. But two and a half years is just right. We are all interested in a completely other news. The new theatre building on Andriivskyi descent is not good, Trump is an avid wit; corruption is deep-rooted and the genders are still fighting. But we no longer care about the news from the front. The reader gained the immunity from such news. Just as banner advertising on the Internet, you just stop to notice.

Susan Sontag in her book We look at other people's suffering writes: "Suffering scenes globalization can encourage people to ‘attend more’. On the other hand, to lodge a sense that the suffering and misery are too enormous, inevitable, inclusive and the local political actions cannot reduce them significantly.” And she continues, drawing an analogy with harm of smoking advertising: "Whether the shock has time limits? Shock can become habitual. Shock can disappear. Even if this does not happen, you can just not look (at this ad. - Platfor.ma). People have a means of protection from distress. In this case from the unpleasant information, if a person wants to continue smoking. It seems normal, i.e. adaptation. As for getting used to the horrible in real life, so you can get used to the horror of some of the images." Or the news, as in our case.

But after all, the war is not a thing in itself. This is a wave that has devastating consequences both during the war and after the end of it. One of these effects has been the massive displacement of people from the Donbas. Among them are 230 thousand children. Media ceased to write about it, relevant ministries slowed down their responses and people again started solving their problems. But the catastrophe remained; the issue has not been resolved.

When I went to the East, I talked with internal migrants who moved from Donetsk and Vodiane to Sloviansk, which was already calm and safe in 2015. All these people had nowhere to return. I talked with mother of four little children, who live with them and another family in a room of 15 square meters. I spoke with people who were moving from one small village to another that is more secure with the hope to return home one day. I talked to a girl in a wheelchair, and then I learned that a few days later a shell hit her house.

Among the cities that I visited was Mariinka. At one time, this name sounded frequently in the news. The city was badly damaged. The entire infrastructure was destroyed. I was talking with a woman while transferring humanitarian assistance. She took me to their house, more precisely to their basement. I went there because all the children that were in the house remained constantly in a tiny basement because it was safer there.

There was musty air and a row of chairs in the corridor, similar to those that were in the hall of my school. Behind a curtain made of old blankets is a small room where the children sleep on bunk beds. She has three children, one her own and two orphans for whom she cares after their parents died a few years ago. There was warm clothing and food stocks there. The mother asks the child to bring his toys to show. Seven-year-old Danila puts on airs, posing for the camera, and then joyfully runs to meet me to boast of the things he has. There are sleeves of different sizes in a cardboard box. These are his toys. He enumerates them and shows them – and then he gives them to me.

There were almost no people in the village Tonenke. Not more than 30 people remained of the 250 who lived there previously. We managed to meet only three families, two of which had little children. Their houses are opposite each other. The girls are friendly neighbours but sometimes they quarrel and do not speak for several days. Diana is six; Anya is three. Anya dreams of becoming a fairy. Her father shows me a battered piece of shrapnel that has become a fence. Diana's grandmother shows me a plastic children's kitchen, all stitched with metal.

Children play on the streets of Pervomaisky just in the middle of the road. There are local residents and settlers from Vodiane, Donetsk, Horlivka. They all play, but as soon as the conversation comes to war, their faces sour and their glances become adult rather and childlike. Most of them have been sleeping in basements already for a year. Four-year-old Kirill speaking about the volleys of hail says it was thunder. It means it will rain soon. But it doesn't rain. There are only new explosions.

.jpg) Picture: Picture: "Odіssea Donbas" Project

Picture: Picture: "Odіssea Donbas" Project

I returned from Donbas in complete disarray. I just didn't realize how serious it was until I myself felt fear of a projectile exploding nearby. Or until I took in my hand a little soft palm and I saw these children with fearless - and sometimes hopeless - eyes.

Upon arrival, I organized with volunteer Ira Soloshenko and colleagues an art auction and we raised almost 2 million UAH to help the children of Maryinka. As a result, the school and the hospital were repaired for the children, a help for them until now. But how many are there that no one helped?

When I talked with displaced persons in Donbas, they all kept saying the same things. They say that the State abandoned them. The ability to move was given to them at the time of the attacks, but the people from sanatoriums and hospitals where they huddle are not happy with the migrants. And they barely have enough money for food and medicines. It's not strange, because the social assistance for the migrants today is 884 UAH per month. So they wait until "it becomes quieter" for a chance to return home. Home they see as a place where you have all you need and you don't need to buy every single thing with your last money.

But they spend. And they are not at home. And people in Kharkiv, Dnipro, Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities speak of migrants in a completely different way. They basically say the migrants, of course, "came in large numbers.” They are louts and let them already go back as soon as possible. And, of course, they can also be understood. Some have loans, some care for sick relatives, care for children, have problems at work, and so on. How can they solve the issues with the displaced persons in addition to their own needs.

But think about it. You have a fire in your street. Your neighbor's house is destroyed and your house have somehow been spared. And instead of helping him, you close the door, and even say something very unpleasant. But now imagine that the other way round – that it was your house that burned down and you need help.

Every day we are rude to each other, and then complain that the migrants are louts. Really? And before that you met only respectable aristocrats in a taxi, in a local building-utilities administrator office, post office and in trams? Perhaps the fact we meet rudeness everywhere doesn't depend on migrants. Maybe they just came, the population has raised, and therefore, this problem has become noticeable? In fact, harsh language and rudeness are always more readily noticed.

I was born and raised in Luhansk. And I can say with confidence that the people from the East are not different from people in the West, except for the circumstances in which they find themselves. Yes, there are some differences in the traditions and the culture attributes. But we all share common values, we have similar habits and we want the same things: safety and comfort.

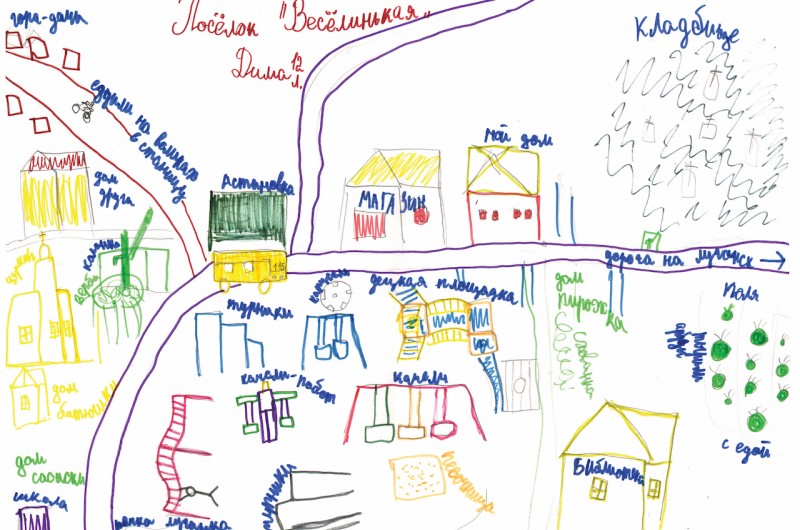

Children are the group that is most severely affected by the crisis. Among them are babies and teenagers. For each age group, moving to a new place is incredibly stressful. The smallest never remember their real home, and nobody knows how long they will live in temporary locations for displaced persons. Now many of them do not have their own rooms, no playground or sports ground near the house, and perhaps not even a table at which you can do you school homework.

More than 100,000 children in Ukraine who have left their homes in the East are growing in challenging economic and psychological conditions. Their habits are formed there and they form new and different values. They will grow up and it is likely they will arrange their lives, but what will be their memories; how will they remember their childhood?

It's time to look at migrants not only as a consequence of the conflict, but as an opportunity for peace development. Imagine that all of these quarter of a million children will grow up and become tomorrow’s scientists, musicians and artists. With new, adequate policies, they will build new businesses and a new country – or they will not. There is also the possibility that we will not give them the opportunity to develop normally, and will go on treating them as enemies.

On December 10, the exhibition "What Is Your Name?" will be opened in Mystetsky Arsenal. We hope to draw the attention of Ukrainians to the problem of internally displaced persons. Our target audience is everyone. We want those who had to endure the relocation, and those who took displaced persons come to the exhibition, those who are open and those not yet ready for dialogue. After all, we believe that art is the place where a dialogue can begin.